Brand & Ad Restrictions in the Global Wine Sector

Motivations, Strategies, Risks, and Responses

The prohibition and temperance movement is alive and well in Canada and around the world. Internationally, wine and beverage alcohol are under threat from groups wholly opposed to its promotion, sale and consumption, period.

This post is adapted from a presentation I delivered October 8, 2022 to the International Wine Law Association / Association Internationale des Juristes du Droit de la Vigne et du Vin (AIDV) annual global conference in Madeira, Portugal. I was pleased to take part on an international panel that set out the systemic risks to beverage alcohol in general, and the wine sector in particular from activist opponents of liquor, focusing on branding / labelling and advertising restrictions.

Together with a country-by-country overview of labelling and advertising restrictions by the International Trademark Association (INTA), and an analysis of France’s Loi Evin (restrictions on liquor advertising) by the Comité Interprofessionnel du Vin de Champagne, I presented a strategic risk assessment for the wine sector from a Canadian perspective, grounded in my years in the natural resource sectors, studying and responding to the strategies deployed by environmental opponents to extractive resources.

The Top (and Bottom) Line

Reasonable and responsible messages of moderation by wine sector representatives and regulators seek to curtail excess, “anti-social” or dangerous drinking. This is an appropriate and responsible strategy, given the harms that can and do come from abuse of alcohol. However, to believe curbing problem drinking is the sole objective of anti-alcohol groups is to miss the mark: a motivated interest group opposed to the sector’s very existence will never accept as satisfactory an end state short of a practical ban on beverage alcohol consumption.

The Canadian Framework

Both federal and provincial governments have authority over labelling and advertising (my reference province is British Columbia). The legal and regulatory frameworks for labelling and advertising wine in Canada are summarised in the below two slides (my emphasis added in red/italics). Provincially, the B.C. Liquor Distribution Branch reviews labelling and the B.C. Liquor and Cannabis Regulation Branch sets promotion and advertising policy, both with reference to “social responsibility” priorities (abbreviated list):

With the regulatory setting as our backdrop, we turn to the motivations, strategies and tactics of groups opposing the advertising, sale and consumption of liquor in Canada.

Motivations

Opposition by advocacy groups is motivated by the desire to end or severely limit the consumption of beverage alcohol.

In Canada, prohibitionism and temperance are alive and well. British Columbians will recall the abrupt, late-hour cancellation of New Year’s Eve 2020. By this phase of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Provincial Health Officer and Ministry of Health leadership knew the impact of public-policymaking, and in the view of many citizens (let alone restaurant and beverage sector operators), the curtailment of liquor sales and service after 8:00 pm on December 31, 2020 was draconian and motivated by more than a concern for transmission of the virus. Had prohibitionist groups achieved a policy “win” through their lobbying?

Strategies

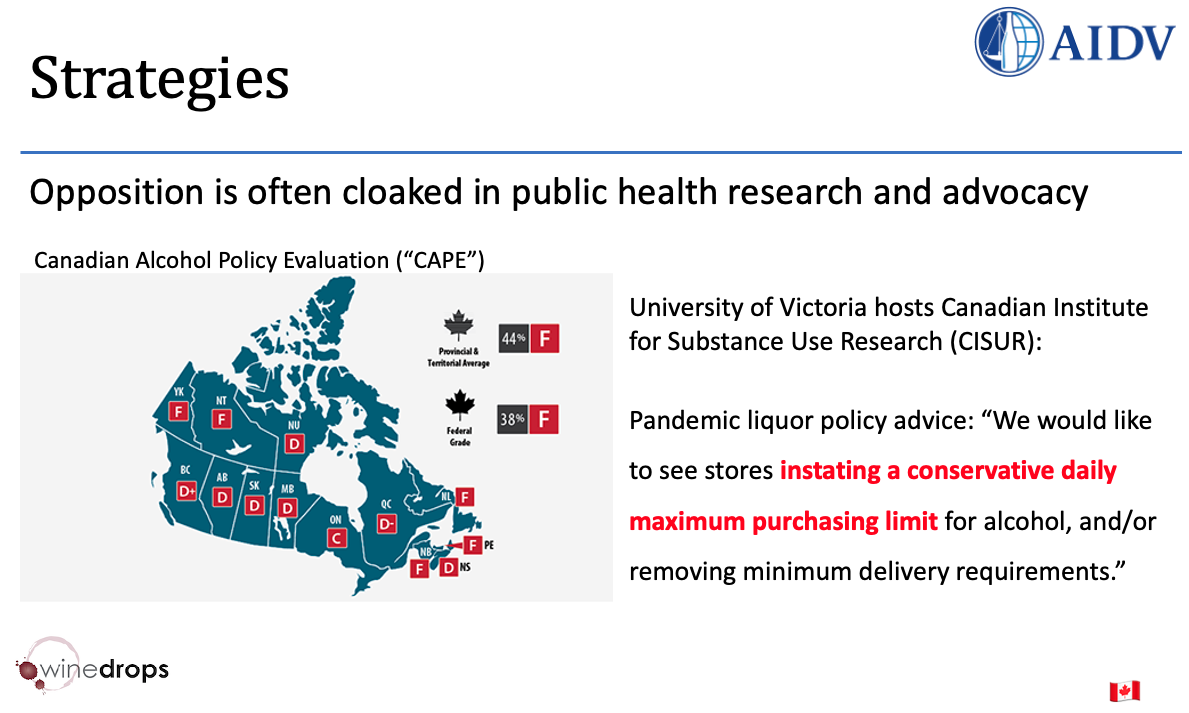

Opposition to beverage alcohol is often cloaked in the guise of public health advocacy. Two prongs of this effort are: policy advice aimed at governments, and campaigns aimed at moving public opinion against beverage alcohol. (Alert: the firms and families producing wine and other beverage alcohol will soon be in the sights of opponent groups). A number of organisations, relying on science of mixed credibility and quality, produce policy advice papers directed to levels of government – often using funding provided by these governments to promote their agenda.

Such organisations generate some valuable information around mitigating problem drinking and shine a spotlight on related social harms from substance abuse. However, they can - and do - overreach from genuine low-risk strategies to severe curtailment, without sufficient evidence or perspective.

In this realm, the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research uses its platform not only to issue annual letter grades to provinces on their liquor regulatory performance (letter grades ranged from D to F, except Ontario which received a C), but also to prescribe pandemic liquor policy advice: limiting quantities purchased by consumers, and disallowing retailers from setting minimum delivery quantities.

On the public campaign front, opposition groups take the approach of “persuasion (or demonization) disguised as information”. In August 2022, the Canadian Centre on Substance Use and Addiction made national headlines when it released its Update of Canada’s Low Risk Alcohol Drinking Guidelines. Open for public comment for just short of a month (in late summer when potential respondents were enjoying their vacations), the Update was presented as a tool for informed consumer decision making regarding their drinking habits.

In fact, its recommended level of consumption shifted from its previous level of three standard drinks per day for men and two standard drinks for women per day, to a flat two standard drinks PER WEEK. The accompanying research (assessment of the increase in harm it detects in public behaviour) does not justify the recommended policy shift.

Recommendations like these have the potential for a rebound effect: not only do they “lose” segments of the public because the research doesn’t adequately connect the apparent risk to the recommended reduction in consumption; but also the message is discounted by many people who don’t regard themselves as problem drinkers just because they exceed the arbitrary threshold of two drinks per week.

Anti-alcohol public campaigns take inspiration from both anti-tobacco advocacy and environmental groups’ campaigns opposing energy and all extractive resources, each of which cite the others in their strategies. In some ways, B.C. is a global ground zero for this nexus: being both the birthplace of Greenpeace and a province of significant natural resources, including timber and other forest products, metals, minerals, natural gas, and water.

Tactics

The tactics of government advocacy campaigns include incremental legislative or rule changes regarding advertising, branding or labelling of wine and beverage alcohol. Other countries, notably Australia, have experienced a dramatic change over 20 years in the label space permitted (front and back) on cigarette packaging, and more recently wine labelling, for information identifying and describing the product. The constriction of the rights of producers to own the real estate on their products and portray its benefits - within reasonable limits - for consumers is considered an existential issue by the International Trademark Association.

Along this line, a recent proposal by Canadian anti-tobacco advocates – which was accepted by federal Minister of Mental Health and Addictions Carolyn Bennett for consideration – would include a world-first requirement that every cigarette sold in Canada be marked with the suggested phrase “poison in every puff”. Is a wine- or alcohol-analogous tactic around the corner? Will advocates claim that every bottle – or every glass – be similarly marked?

The tactics of public campaigns include moving opinion – sometimes incrementally, sometimes significantly, as in the attempt referenced above by the CCSA to reclassify all levels of consumption above two per week as “problem” drinking – through simplification of messages of alcohol harms, and by demonization: deliberately blurring the lines between the serious societal and public health impacts of problem drinking and moderate or occasionally elevated social consumption of alcohol.

Wine Sector Risks

The most significant risk for the sector in engaging and accommodating opponents of alcohol is that the goalposts are always moving. As many operators in Canada’s natural resource sectors have experienced for many years, in the endless negotiation between a given sector and a motivated interest group opposed to that sector’s very existence, there will never be an end state that is satisfactory to the opposition movement. An industry can exhaust many hours (years) of effort through engagement, attempts to conciliate or reconcile points of contention – such as beverage alcohol sponsorship or advertising at cultural, family or sporting events – and achieve apparent agreement, only to learn that this level of activity (which may be voluntarily circumscribed by the sector itself) is no longer acceptable. And the cycle begins again, with demands continuing to ratchet up.

Wine Sector Responses

In Canada, the national wine sector representative organisation WineGrowers Canada (together with constituent provincial winery associations) produces a campaign called The Right Amount, which provides moderate drinking guidelines and a standard drink calculator. In B.C., the Liquor Distribution Branch (as liquor regulator, distributor of record and operator of a chain of retail outlets) also conducts a campaign at on-premise locations “Why Another?” to encourage consumers to think again before ordering another drink.

Moderation messages by wine sector representative bodies make sense in a normal context: guidelines for moderate drinking and information about the alcohol content in a standard drink are responsible and reasonable for a product that can cause harm and therefore needs to be regulated. In practice, voluntary restrictive steps are risky, as they put the sector on the back foot vis-à-vis anti-alcohol groups, which in turn perceive an advantage and continue to press for ever more restrictive practices.

How to Respond: a Call to Action

The above discussion, together with the constrictive labelling and advertising shifts in recent years around the world (as presented by INTA and the Comité Champagne, among other organisations tracking such developments such as FIVS (international trade organisation of wine and other fermented beverages)) prompts a “Beware” flashing warning light. My advice is that it be heeded by legal and business advisors to wine and beverage businesses, their representative bodies, and regulators.

A more holistic perspective on the role of beverage alcohol in society is in order, to ensure the pendulum does not swing too far in the prohibition direction. Adverse health effects from problem drinking are widely understood and generally taken seriously. However, the prohibition / temperance movement narrowly centres its messaging on these harms as being as applicable to the general public as to those at high risk of developing a dependency; and deliberately neglects the social, societal and psychological benefits of the odd tipple.

University of British Columbia Professor of Philosophy Edward Slingerland reminds us in his 2021 book “Drunk” that beverage alcohol has been an enabler of civilisation(s) for ~8,000 years and counting, and that evolution has not yet eliminated the taste for alcohol from our motivational system. Is it an evolutionary accident or hangover? Slingerland argues it is not, and that evidence is provided from archaeology, history, cognitive neuroscience, social psychology, literature and genetics to underpin a rigourous understanding of the place of alcoholic beverages in civilisation.

My strategic advice to the Canadian and global wine sector is not to debate the opponents of alcohol directly on the narrow but complex scientific questions of harms to health.

Rather, a strategy for the wine sector and its professional advisors is that it be nuanced and moderate: in the main, it would remind customers, regulators, government policymakers, and yes, opponents, that wine plays a role as a place-based, fresh-grape fermented agricultural product - often made by families and small businesses - to be enjoyed with food; that it promotes a cultural identity and is a significant tourism attribute; that it promotes innovation and creative thinking; and that it marks special occasions and contributes to the fabric of family, professional and social connections.

If these occasions and connections aren’t needed in these turbulent 21st century times, when are they? The answer, it turns out, is: throughout human history.

If you wish to receive all WineDrops posts, please join the mailing list here: https://winedrops.ca/contact.