Unlocking the Value of Canadian Wine Appellations

Recent European Union research explains why Canada’s wine regions should pursue an Appellation/Geographic Indication strategy.

The challenges facing Canada’s wine industry, in the context of rising taxes and less preferential access to home markets (Canada’s response to Australia’s challenge at the World Trade Organisation), not to mention pandemic-induced trade channel disruption and persistent internal trade barriers, imply Canadian wine-producing regions need to work harder to promote and sell their wines from the standpoint of quality and unique reputation.

Alongside short-term survival strategies, they could do worse than pursue a long-term strategy that evokes the origin and sense of place for their wines: in other words, double down on the emerging appellation and geographic indication regimes in British Columbia, Ontario, Québec and Nova Scotia. It turns out this could be highly profitable, if pursued with single-minded purpose and a long-term focus by Canada’s wineries and their regional marketing bodies.

European GIs are far ahead…

In late 2019, the European Commission’s Directorate General for Agriculture and Rural Development published a useful analysis of the value impact – and value premium rate – of Geographic Indications (GIs) in wine in European and international markets.

The October 2019 EC Study on economic value of EU quality schemes, geographical indications (GIs) and traditional specialities guaranteed (TSGs) illustrated that there is a value increase of wine sales associated with protected GIs. The study reviewed sales data for the EU-28 Member States across the relevant product classes between 2010 and 2017.* It analysed the boost in sales value and volume over time due to GI-protected wine production. Further, the study estimated the “value premium” by each wine-producing member state for GI wine. Findings are below:

As shown in Table 1, the value of sales of GI-protected wine within the European market increased by 33% between 2010 and 2017 (and 43% from the previous study in 2005). Approximately 30% of the increase in value over the study period is driven by the GI regimes of powerhouse wine countries France and Italy. The volume increase in EU-28 wine sales was approximately four percent, which speaks to the significant price premium associated with well-established GI schemes. (The study notes that Member States have varying orientations toward GI-protected wine production: most major wine producing countries are "balanced" between 30% & 80% of GI versus non-GI wine production, e.g. France, Italy, Spain and Portugal).

The value of GI-protected wine exports to non-EU countries was up even more significantly than EU-28 sales, increasing by 70% between 2010 and 2017 (29% by volume over the same period). In 2017, the value of exports of all EU wine was EUR 11.3 billion , and nearly 76% of that was GI-protected wine. Exports of GI-protected wine accounted for only 57% of volume, illustrating the premium reputation of GI wines, and the strong demand for them in overseas markets.

Perhaps more interesting than the value impact of GI schemes on wine sales is the Value Premium Rate (VPR), which indicates by how much the value is elevated for wines produced in a given GI-protected region compared to wines that are not GI-protected. Essentially, the VPR represents the potential monetisation of reputation and influence that GI schemes bring over time to wines produced by major European countries.

Figure 45 of the European Commission study (at p. 102) identifies the average VPR for the EU-28 for wine, spirits and agricultural products in 2010 and 2017. Wine accounts for 65% of the value premium across the three product groups, at EUR 25 billion. While the average EU rate for wine increased to 2.85, there is a wide variation in the premium rate among wine-producing Member States.

The chart below (Figure 50 of the European Commission study, p. 109) breaks down the VPR for wine by Member State. Unsurprisingly, among the major producers France has the highest value premium rate at 4.13 followed by Spain at 3.06, while Germany, Italy and Portugal fall just below the EU average, ranging from 2.57 to 2.07.

… But Canada has a good foundation on which to build

Over the past decade and more, Canadian wine-producing regions have begun to implement Appellations or GIs (different terms are used in different provinces) to delineate wine-producing areas that exhibit specific and identifiable quality characteristics in the wines. As vineyards mature, the wines they produce can express their terroir, their microclimate and more.

The establishment of Appellations and GIs helps wine producers hone their quality and stylistic programmes, and of course helps them market the wines. For consumers, the establishment of GIs/Appellations improves awareness and understanding of the wines from various regions, and brings them along on the journey of a maturing wine industry. For a number of years in British Columbia and Ontario, the “Okanagan Valley” GI and the “Niagara Peninsula” Appellation were used to identify where the wines came from. Unfortunately these GI/Appellations represent very large geographic areas: B.C.’s Okanagan Valley is approximately 200 kilometres/125 miles long, and Ontario’s Niagara Peninsula holds some 5,500 hectares/13,600 acres of vines.

Fortunately, many wine producers have been keen to establish Sub-GIs (B.C.) or Sub-Appellations (Ontario) to further delineate the specific places and unique characteristics of their wines. For example, today Niagara hosts ten Sub-Appellations and the Okanagan hosts four Sub-GIs. In addition, Québec has a Protected Geographic Indication “Québec Wine” Zone, within which it has seven wine growing regions. Nova Scotia has a provincial “Nova Scotia” GI, and in addition to its first appellation “Tidal Bay” there are six wine regions around the province.

It will – and should! – take a long time for the emerging GI schemes in Canada’s wine-producing provinces to approximate the powerhouse appellations such as Bordeaux and Burgundy (and their critically important sub-appellations) that are recognised and demanded around the world. Credibility and reputation are built slowly, and the quality wines produced in GI-protected Canadian wine regions will be judged vintage after vintage until their track record for quality, expression of unique place and consistency (and perhaps other characteristics) are fully established – and have gained a following that will pay a significant premium for the wines.

Canada’s Potential, Canada’s To-Do List

What value premiums could Canadian GIs, sub-GIs, Appellations and Sub-Appellations deliver? To properly answer this question requires a deeper analysis than is possible here – beginning with the price and volume statistics for wines presently produced under the GIs and Appellations today, and then projecting their potential future value through scenario analyses.

However, we can conduct a thought experiment: If Canada’s wine regions aggressively pursue a GI/Appellation strategy over the next decade or two, we can use the EU value premium findings to project what is achievable for wines produced in GI-protected areas. Further, we can expect that a Value Premium Rate is not static, and should slide higher on the scale as wines from a given GI become more sought-after. Even if not completely accurate, estimating the premium rate based on EU findings can set a useful quantitative goal for Canadian Appellation and GI regions.

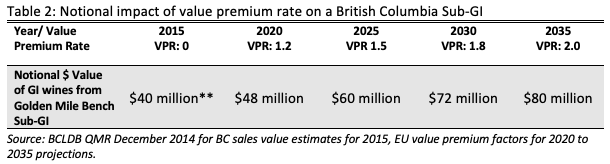

For example, if we took the Golden Mile Bench – the first B.C. Sub-GI to be approved in the Okanagan Valley (2015) – and ascribed at first a relatively low VPR which increases gradually over time, we can estimate a value premium available because the wines were produced in the Sub-GI. For this very simple experiment in Table 2 below, we hold volume constant (the EU formula is complex and takes account of volume and value of GI and non-GI wine, all of which change over time). We also disregard other input factors to the final price of a bottle of premium wine such as land and grape costs, as well as labour and other input costs, most of which rise over time. A VPR of 2.0 means that the price premium a producer can command in a Sub-GI like the Golden Mile Bench doubles the top-line revenue.

The general lesson from the EU study is that if all Canadian GIs and Appellations pursue an appropriate strategy - assuming the product in the bottle delivers the requisite quality improvements - protected regions should experience the financial benefit of commanding a material premium for their wines.

There is a To-Do list attached to this strategy. The first item is to build a governance and administrative architecture for each province’s Appellation or GI system. This is an essential step to establish reputation and credibility on which future value gains will rest.

For example, here in British Columbia the B.C. Wine Authority conducts the evaluation for a new sub-GI application and makes a recommendation to government to approve an application. However, there is not yet in place a governance or administrative function after a Sub-GI is established. The B.C. Wine Authority is empowered to ensure compliance through labelling, but as yet there is no other monitoring or compliance system in place to assure that individual wineries adhere to the standards and terms of a new Sub-GI.

Is it the job of the B.C. Wine Authority to do so? Perhaps, but government and the industry at large will need to answer this question and allocate new financial and human resources accordingly. Once this architecture is in place, industry marketing bodies such as the B.C. Wine Institute can pursue their mandate with heightened confidence that the GI and sub-GI system in the province is robust.

The rest of the To-Do list flows from action plans by provincial and regional wine marketing bodies, and of course the producers themselves who are pursuing a premiumisation strategy. A significant lesson from the EU data: the value premium derived from GI-protected regions can drive a very significant boost in price for exported wines. Canada’s export strategy should be designed to increasingly emphasise GI-protected wines as they come into their own over the years, to maximise the available premium.

The opportunity seems limitless, but the competition from established and other rising wine regions around the world will be fierce. Canadian wine has a tremendous opportunity to enhance wine value and reputation through an appellation and geographic indication strategy. The industry will need to bring its “A” game, and prepare to play the long game.

* The analytical method in the EU study compared the price premium and value premium rate for GI wines (1,576 products) compared to those without a GI scheme, in both volume and value. Sales were calculated at the wholesale stage in the market (i.e. excluding transportation and taxes). Many nuances and detailed calculations in the real-world marketplace are likely missing from the EU’s analysis, and are certainly omitted from my very brief overview and summary. But the premiums and premium rates estimated in the EU study are nonetheless directionally useful.

** The $40 million notional sales estimate for wineries in the Golden Mile Bench in 2015 is based very roughly on December 2014 BCLDB Quarterly Market Review tables, which showed BC wine sales in the range of $400 million. I have estimated - for illustrative purposes only - that the Golden Mile Bench represented 10% of that figure.

If you wish to receive all WineDrops posts, please join the mailing list here: https://winedrops.ca/contact.